It would not be an overreach to say that in India as in many parts of the world, it is the children who were the first victims of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the cases began to increase in the second week of March 2020, schools were the first to close down.

One-and-a-half years later, in India, students continue to be confined to online schooling; many have dropped out altogether. This, as offices and commercial establishments are opening up. Indeed, the duration of school closures in India has been among the longest in the world, according to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

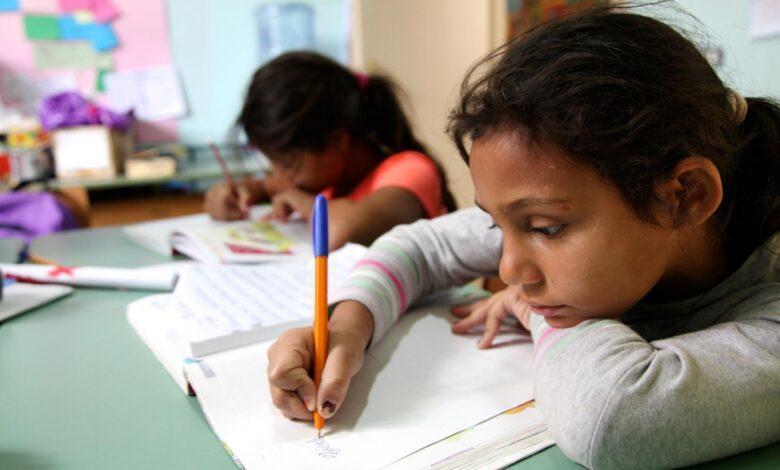

As students were left with no choice but to accustom themselves to the “new normal” of online schooling, pre-existing learning inequalities were magnified. These gaps, brought about by socio-economic differences, manifested themselves in educational access, participation rates, and learning outcomes.

With online and remote learning being far less effective than the teacher-driven, physical classroom mode, students have suffered what a report by Azim Premji University called “regression in learning”. According to the report, the experience is shared across India’s vast socio-economic spectrum.

The severe effects of pandemic-induced education divide and learning loss will impact an entire generation of students. There is a need to recognise it early and make swift, serious course corrections.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), some 250 million children enrolled in elementary and secondary schools across India, and another 28 million aged 3-6 years in early-childhood education, have been affected by school closures.

In rural India, the ASER (Rural) 2020 Wave I survey found, the proportion of “out of school children” has increased from 1.8 percent to 5.3 percent in the 6-10 age group between 2018-2020. Given that about 90 million children in the rural districts were enrolled during the year prior to the pandemic, out-of-school rural children are likely to have increased to three million.

In the capital, Delhi, the government has reported that close to 15 percent of students in government schools have not been “traceable” since the initial lockdown in March 2020. Part of this number may be those who have reverse-migrated with their families.

Girls at greater risk

A sizable portion of these children whose families had no option but to leave the city during the initial lockdown, could fail to re-join school if they are not provided with additional support.

Girls are at greater risk of dropping out, especially in the secondary grades of 9 and 10: analysis by the Right to Education Forum estimates that some 10 million secondary-school girls are at risk of dropping out due to the pandemic. This can set back India’s efforts at promoting the welfare of girls, as there is enough evidence that keeping them in school protects girls from various threats like early marriage.

Education in Crisis: Before and After COVID-19

Prior to the pandemic, education stakeholders were primarily concerned with what they called the “crisis of learning” in India, which they described as “endemic”. While the country had largely achieved Universal Access, Enrolment, and Retention in elementary education, its children were lagging even in basic grade-appropriate reading and arithmetic skills, as noted by the annual ASER surveys (Rural) from 2005 to 2018.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, approved in July 2020, responded to this concern by stressing that “attaining foundational literacy and numeracy for all children must become an immediate national mission.”

By then, a nationwide lockdown had been implemented as a response to the spread of COVID-19. Schools were closed, and consequently there was a rapid increase in the use of remote-education resources—both old media (radio and television), and new (online classrooms, YouTube videos, and messaging service WhatsApp).

In September 2020, a UNICEF Rapid Assessment of Learning during School Closures found that only 60 percent of children had utilised distance-learning resources in the preceding six months.

The Wave-1 of the ASER (2020) survey also reported that a mere 18.3 percent of children in rural areas enrolled in government schools have accessed video recordings, and 8.1 percent have attended live online classes. The proportion slightly rises to 28.7 percent and 17.7 percent for rural children enrolled in private schools.

Even with the best resources, remote learning with digital aids has been less effective than classroom learning. Teachers are convinced that remote learning cannot mirror school-based learning, and want schools to be reopened as soon as possible. There is also no dearth of anecdotal evidence that parents, and children themselves, have repeatedly expressed their desire to have schools reopened.